Of all the pirate stories handed down to us across the centuries, those from the “Golden Age of Piracy”

Of all the pirate stories handed down to us across the centuries, those from the “Golden Age of Piracy”

(approximately 1715 -1725) are perhaps the best known, mainly because they are so well documented. The drama that unfolded throughout the islands of the West Indies helped shape the future of colonial empires in the Americas, and is therefore an integral part of our nation’s ‘prenatal’ heritage.

During this period, a particular track of political events, wars, and socioeconomic factors combined with a resourceful brand of lawlessness to forge an alliance based in the Eastern Caribbean known as the ‘Pirates Republic.’ Historically, it might be compared to the days of the American Wild West in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Tales of pirates from this brief period come alive with a singular spirit of bold defiance as old as Homer’s descriptions in The Iliad and The Odyssey. But were it not for the uncertainty of the times, and the assertion of this undaunted spirit, such a world of pirates would never have existed at all.

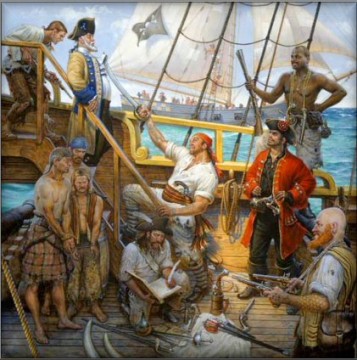

The first crews of the Golden Age of Pirates were made up of willing privateer recruits. Later, they would be composed of sailors from every sort of vessel that sailed the Atlantic. In the best of circumstances, common sailors did hard labor for low wages, and the very nature of their positions put them in constant peril. As time passed, plenty of sailors who joined pirate crews held a deep resentment against the merchantmen and the slave traders with whom they had previously sailed. Often harsh authoritarians who imposed cruel, arbitrary punishments on their crews with few accessible remedies, commanded these vessels. Under successful pirate captains, crews shared a sense of equality, even ‘ownership.’

Although it didn’t spare them from the death penalty if they were caught trying to desert, all were bound by a common oath known as Articles of Regulation (pirate law) that gave them a means to air their grievances. Good thing, because there was a lingering mistrust of leadership among all pirate crews. They were constantly voting leaders in and out, and would resort to whatever means necessary to depose them.

The most admired pirate captains embodied both the best and the worst traits and temperaments of their crews. These leaders had to be bold enough, and clever enough to outmaneuver not only their enemies, but their own demons as well. For the most part, when they weren’t under the influence of an adrenaline ‘fight or flight’ rush, pirates had uneventful lives, sometimes, even boring. Music helped sailors pass the time on board, and was the chief source of inspiration and entertainment.

Musicians were often ‘retained’ from captured vessels, as well as ‘artists’ such as tailors, carpenters, and surgeons for service to both captain and crew. When pirates went after their prey, they had to work together, so harmony among shipmates was a must. If sailors got irritable, and tempers flared, arguments were often settled by dueling. This was not permitted on board the ship, however, and had to be carried out on shore.

After capturing prizes, pirates often retired to some safe harbor where their vessels could be cleaned and repaired. Then the loot was divided, and there was a lot of feasting and drinking. With such ‘addictive highs and destructive lows,’ it’s no wonder that drunkenness was a real problem.

It might be safe to say that outlaws in any age are prone to extinction, but the short, violent lives of many of these young pirates were filled with adventures, pleasures and freedoms about which other men (and women) of those times had not even dreamed.

Throughout most of the Golden Age, neither the constant presence of the Spanish Masters, nor the various periods of manipulation by British, French, Portuguese, and Dutch (European) colonial interests were the most immediate perils for pirates. In the beginning these things actually worked in their favor. The most immediate perils were natural made life in ‘paradise’ almost unbearable; the jungle undergrowth was difficult to maneuver; the ultramarine blue waters of the Caribbean Gulf Stream were swift and full of unpredictable currents; and the threat of tropical disease lurked in every watering pail. Sometimes even earthquakes shook the region. Above all else, nothing was as costly as the hurricanes.

Many pirate vessels and their consorts had a cyclical route of plundering called the ‘pirate round,’ sailing out of the West Indies, and up the American coastline as far as Newfoundland to escape the summer’s heat. Then in the winter, they’d sail southward to the Leeward Islands or Barbados, and lie in wait for the Christmas provision ships. Some of the later pirate crews would even sail to Brazil, Africa and over to the Indian Ocean, before returning to the West Indies to start the round over again. This took them out of the warm waters of the Caribbean during the most threatening months of the year, and often ensured that they wouldn’t get caught in the paths of the biggest storms.

But as we all know, sometimes hurricanes follow a path that takes them right up the eastern seaboard, and at any time of year, smaller storms, and Nor’easters can take their toll. The account that appeared in The General History of the Pyrates of two ferocious gales that pounded Captain Samuel Bellamy and his crew in the Whydah Galley off the coast of the South Carolina in early 1717 stands as a grim reminder. The writer says that during the first storm, the ship was nearly ‘quick going down into Hell,’ and sustained such damage that they were forced to keep the pumps running day and night to get rid of the seawater.

Several weeks later, as they were making their way off a lee shore around the treacherous shoals near Cape Cod, Rhode Island, the Whydah was caught in the second storm. Cape Cod had been Bellamy’s home before he took up piracy, and he often went back up there to visit. This time he was sailing at night with a small fleet of captured ships, one of which was ‘a pink’ named the Mary Anne. The master of the Mary Anne had been left on board his ship, and when the fleet was separated by high seas and blinding rain, the Mary Anne ran aground.

Seeing the ship’s light, but not the shoreline, the Whydah followed. It is believed that Bellamy and his crew were intentionally lured into shallow waters by the master of the Mary Anne, who deliberately ran his own vessel aground in order to trick the pirates into following him to their destruction. Whatever happened it was enough to doom the wounded Whydah, as the force of the fierce winds off the Atlantic continued to push the large square-rigged galley towards the shore. Several miles up the coast, she was blown into a rocky shoal, broken apart by the pounding breakers … and went down.

The boastful Samuel Bellamy, who spoke what the hearts and minds of many pirates believed, had just days before vehemently proclaimed, “I am a free prince, and I have as much authority to make war on the whole world, as he who has a hundred sail of ships at sea, and an army of 100,000 men in the field, and this my conscience tells me…” But on that stormy April night, off the coast of Cape Cod, Bellamy went down with his ship, along with 144 members of his crew. It was every pirate’s nightmare come true. As news of the tragedy spread throughout the Pirates Republic, it was quite a sobering moment.

Ironically, more pirate ships were destroyed by such storms and other ‘acts of God,’ or by the pirates, themselves, than were ever captured by the British Royal Navy before 1718. Contemporary author Peter Earle points out in The Pirate Wars (2003) that during the War of the Spanish Succession, and the Jacobite Rebellion, Britain was reluctant to send ships to the West Indies, because they were needed elsewhere. Many of the pirates were also Jacobite sympathizers, who would attack any British ship that sailed into the region. It was under those circumstances that the privateers and the pirates kept the shipping lanes open, fought their own private wars with the Spanish, and turned profits from stolen Spanish goods into their own local ‘pirate economy’.

For years, that was the order of things. After all, as David Cordingly tells us in Under The Black Flag (1996), even when the young Welch privateer, Henry Morgan first arrived in the West Indies in 1654, he was part of a British expedition sent out to capture Spanish Hispaniola. When the attempt failed, they decided to attack the less-fortified island of Jamaica. They were successful, and Jamaica became a British settlement that evolved into one of the most important bases of operations for the Royal Navy against the Spanish during those early years.

Morgan was given letters of marquee (commissions) from the Governor of Jamaica and carried out many raids against Spanish possessions in Central America, with the blessings of the Cromwell and the English Crown. Then at age thirty-two, Henry Morgan was made Admiral of the original ‘Brethren of the Coast,’ a loose and diverse association of French, Dutch and English privateers and pirates from Tortuga, who worked together to carry out raids on Spanish ports and towns, rather than attack ships. They operated under a strict, but remarkably democratic code known as the ‘Law of the Coast,’ and shared the spoils of their efforts. Many of these ‘buccaneers,’ as they were also called, were excellent marksmen who carried French muskets rather than swords and cutlasses, as later pirates did.

Captain Henry Morgan is often called the ‘King of the Pirates,’ because of the depth and breadth of allegiance sworn to him by so many of his contemporaries. After uniting the privateers of Jamaica with the ‘Brothers’ from Tortuga, he sailed with some two thousand ‘wild men,’ and one woman who was purported to be a witch, and commanded a fleet of thirty-eight ragtag buccaneer ships and boats in his last campaign to Panama. However, this last ‘big adventure’ got Morgan (and the Governor of Jamaica who issued the commission) into big trouble. At the time of the sacking of Panama, England was supposed to have been officially at peace with Spain after signing the Treaty of Madrid in 1660. In an attempt to distance themselves from the incident, British authorities called for Morgan’s arrest.

Captain Henry Morgan is often called the ‘King of the Pirates,’ because of the depth and breadth of allegiance sworn to him by so many of his contemporaries. After uniting the privateers of Jamaica with the ‘Brothers’ from Tortuga, he sailed with some two thousand ‘wild men,’ and one woman who was purported to be a witch, and commanded a fleet of thirty-eight ragtag buccaneer ships and boats in his last campaign to Panama. However, this last ‘big adventure’ got Morgan (and the Governor of Jamaica who issued the commission) into big trouble. At the time of the sacking of Panama, England was supposed to have been officially at peace with Spain after signing the Treaty of Madrid in 1660. In an attempt to distance themselves from the incident, British authorities called for Morgan’s arrest.During those years, the war with Spain was rekindled several times, and the French were also hostile. At one point, the settlement at Nassau had been plundered and burned three times, and the people there were left to fend for themselves. But according to Peter Earle, since there were only occasional and minor complaints about a few of the ‘masterless men’ like Benjamin Hornigold at Nassau, England was not that interested in ‘small scale villains, so far away.’

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

So arose the pinnacle of the Pirates Republic, with its infamous circle of captain cohorts, Henry Jennings, Ben Hornigold, Bart Roberts, Sam Bellamy, Charles Vane and Edward Teach (or Thatch), as well as many smaller operators like Calico Jack Rackham (with Anne Bonny and Mary Read) and James Bonny. But after several seasons of ‘lawlessness,’ London began to wonder if the Bahamas might not be turning into another Madagascar.

The King’s Pardon in 1718 created a short period of relief for British authorities. Some of the outlaws accepted the reprieve, came ashore and stayed there, including Ben Hornigold and Henry Jennings. The rest of them were hell-bent upon ‘sailing under their own flags.’ Attacks against virtually all seagoing vessels along the coasts, and in the shipping lanes of the Atlantic seaboard and Eastern Caribbean reached new heights between 1719 and 1720. When the British finally decided to act, they were decisive. This time, many Royal Naval ships were sent, and authorities began soliciting aid from local captains. Even newly reformed pirates (including Ben Hornigold) became pirate hunters. Suddenly there was a local threat, just as formidable as any hurricane or Spanish fleet … right on the doorstep of the Pirates Republic.

Late in the game, some of the pirates like Captain Bartholomew Roberts and his crew had extended their operations to the coast of West Africa and as far east as the Indian Ocean. But off Cape Lopez, Gabon, in February of 1722, Robert’s gallant ship, Royal Fortune met its fate at the hands of Royal Navy Captain Challoner Ogle, commander of the Swallow. Roberts lost his life, and two hundred sixty-two pirates from two pirate ships were captured in a humiliating defeat. But the body of ‘Black Bart,’ still dressed in his scarlet waistcoat, was thrown over-board by the members of his crew, rather than let it be taken by the British.

Although the last execution of a pirate from the Golden Age on an island in the Indian Ocean didn’t take place until 1730, David Cordingly writes, ‘Of twenty-seven trials held between 1700 and 1728, in only five cases were the executions restricted to the ringleaders…,’ so as the total number of pirates operating in the Atlantic in 1720 was only about two thousand strong, the last days of the Pirates Republic were swift and final.

It’s also interesting to note that when the first city of Port Royal founded in 1650 was completely destroyed in the summer of 1692, four years after Henry Morgan’s death, nearly two thousand lives were lost, and everything in the old city was washed away from its sand foundations by the tsunami. Many to this day believe that such a natural disaster was a form of divine judgment on what had been a hellish ‘pirates’ den of iniquity.’

Although the old town, which remains underwater, was never rebuilt, Port Royal continued as the seat of commerce in Jamaica. The new town survived a fire in 1703, a major hurricane in 1722, and several more earthquakes, before it’s final decline. Nassau was spared the earthquake, survived the fall of the pirate economy, and eventually recovered from frequent abandonment by aggressive British colonial interests.

The robber barons of the Pirates Republic would never again rule the waves, but pirates would, at various times in American history, sail again as heroes. The Patriot, John Paul Jones sought to deter English shipping during the Revolution. Countless others were captured and detained as pirates in British prison ships off the coasts of New England during the War for Independence. Later, the French pirate, Jean Laffite aided General Andrew Jackson in the battle against the British at New Orleans in 1814.

“The Law of the Coast” also survives, and in the early fifties, a group of seven seamen from Chile decided to revisit the tradition. Searching for a means to restore that early spirit of democratic egalitarianism, and preserve the skills and joys of seafaring, they revived the name and formed a fraternity, adopting principles of conduct much like the custom of the coast that guided the original ‘brethren of the coast’ in the seventeenth century.

“The Law of the Coast” also survives, and in the early fifties, a group of seven seamen from Chile decided to revisit the tradition. Searching for a means to restore that early spirit of democratic egalitarianism, and preserve the skills and joys of seafaring, they revived the name and formed a fraternity, adopting principles of conduct much like the custom of the coast that guided the original ‘brethren of the coast’ in the seventeenth century.

As word spread out from Chile, the association quickly grew into an international organization known as Brotherhood of the Coast.‘Tables’ (memberships of at least seven sailing captains to honor the seven founders) now exist in many countries, including the USA.

Flying a single ensign designed specifically for the brotherhood, these twenty-first century buccaneers dress in full regalia at celebrations and share hospitalities all over the world. They strive to affirm the camaraderie of sailing, navigate the seven seas in sailing ships, and promote the preservation of the oceans, worldwide.

In many ways they are very much like the pyrates of old, but unlike the ill-fated outlaws of the Pirates Republic, these modern-day adventurers, along with their families and friends, are free to enjoy the true spirit of universality – the loftier spirit that has accompanied seafaring ever since the days of antiquity!

*Copyright 2012, A Pyrate’s Life for Me – Cynthia Farr Kinkel

(*Elements of the above story have appeared in other publications, including the Sept. 2005 issue of The Tybee Breeze and Sept/Oct 2006 issue of The South Magazine. The content has since undergone several revisions for further publication with additions and updates.)

Excellent work!

Thank you! Appreciate the visit. Looking forward to reading your new book, Quest for Blackbeard! https://www.amazon.com/Quest-Blackbeard-Story-Edward-Thache/dp/136532821X